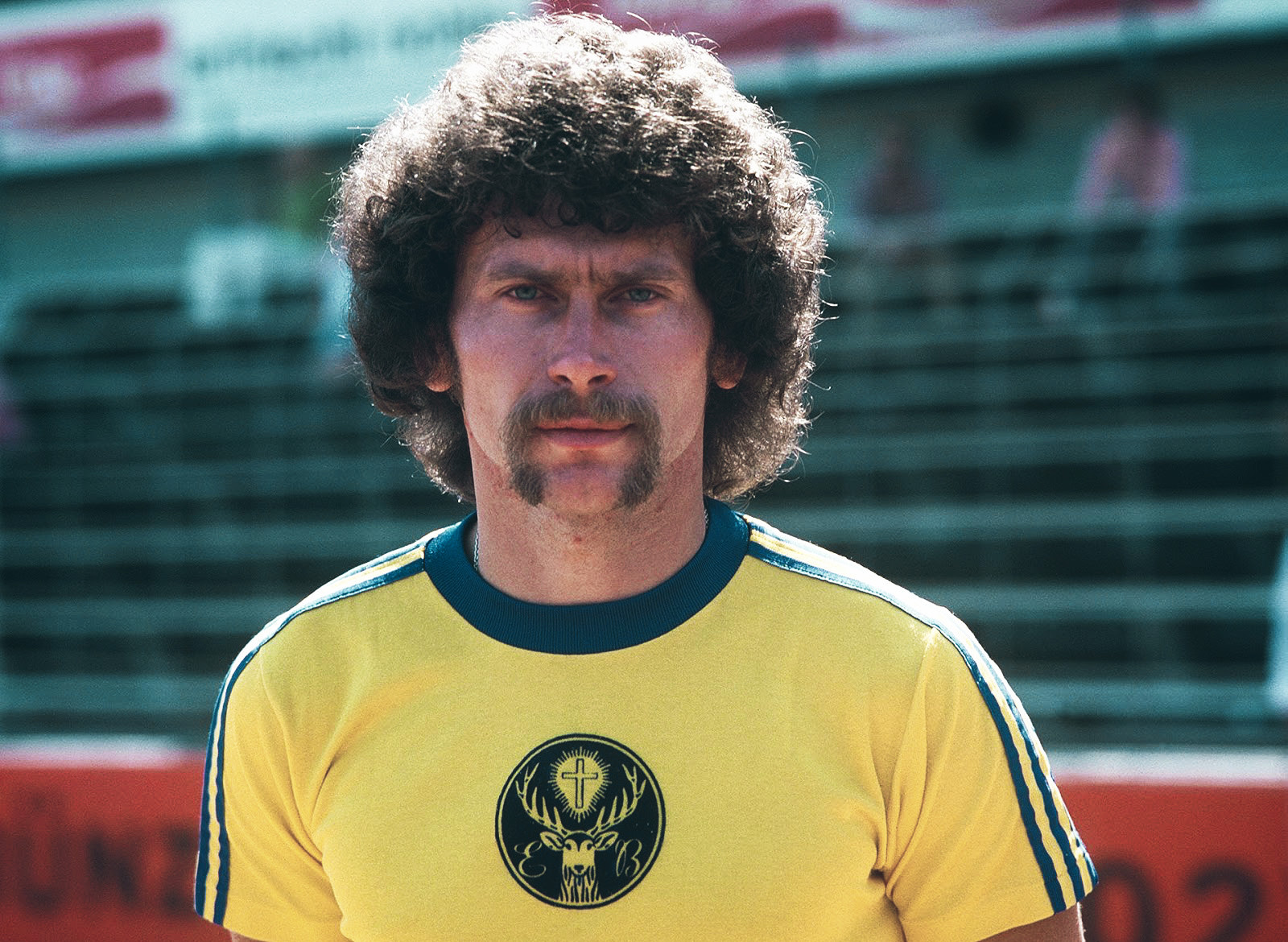

During the late 1960s and early 70s, West German football was the dominant force in the game. As well as Die Mannschaft lifting the World Cup in their homeland in 1974, Bayern Munich brought three successive European Cups to Bavaria between 1974 and 1976. A number of players featured for both Bayern and the national side, and whilst some may be more celebrated – the likes of Franz Beckenbauer and Gerd Müller spring to mind – few would have been more instantly recognisable than Josef-Dieter Maier, better known as Sepp Maier; owner of big gloves, long shorts and a goalkeeper’s cap full to the brim with medals.

The legendary custodian is often acknowledged for his pioneering attitude to the role of the modern man between the sticks and is often particularly lauded for his agility. It’s an skill that earned him the nickname of Die Katze von Anzing – The Cat from Anzig. For all that, though, to the many millions of football fans around the world, it was the seemingly oversized gloves and long shorts Maier that made him one of the most recognisable footballers on the planet.

As his nomme de guerre suggests, there was far more to Sepp Maier than a perhaps questionable choice of attire. He was not only one of the outstanding goalkeepers of his generation, but also an indispensable member of both the club and national teams that ruled football in the 70s.

Sepp Maier was born in the small town of Metten, Bavaria, in February 1944. Growing up in a post-war Germany destroyed by conflict, and then torn asunder by allied rivalries bent on securing their own dominions, would have been a harrowing process. The young Maier had football for solace, however, and his passion for the game would bring great reward. At just eight years of age, he joined local sports club TSV Haar, where his ability was nurtured to the extent that, in 1959, he was snapped up by Bayern Munich.

It was the beginning of a relationship with the club that would stand the test of time. A playing career spanning 18 years was later followed by a further 14 working as a coach and searching for his successor. It was a task that he excelled in, developing and mentoring Oliver Kahn, who would have 14 years with Die Bayern.

At international level, this dedication to his protégé eventually cost him his coaching position with the national team. After Euro 2004, he clashed with then manager Jürgen Klinsmann, who preferred to play Jens Lehmann ahead of the Bayern stopper. With no less 95 caps and an array of honours with Die Mannschaft to support of his opinion, perhaps Klinsmann should have taken greater heed of Maier’s more qualified counsel. He didn’t do so, though, and the two parted company.

Starting off with Bayern’s youth team, Maier progressed through the ranks and international recognition wasn’t slow in following. From 1961 to 1962, he played 11 games for the West Germany youth team and the following year, he also featured four times in the national amateur side. There were surely bigger things ahead for the goalkeeper, now in his late teens.

By 1962 he was in the Bayern first team and would stake a claim for the club’s number one jersey, which would last until 1979, when a car accident brought the curtain down on his career at the age of 35. With other goalkeepers of his era, namely Dino Zoff, playing past the age of 40, there would have been many more games left in Maier had the accident not occurred. In between those dates, though, he would still become one of the great figures of German football.

Unsurprisingly, the peak years of Maier’s career coincided with the most successful periods for both Bayern and West Germany. For his club, it was an ascendancy that took root in his early years as the club blossomed in the decade between 1965 and 1975. DFB-Pokal triumphs in 1966 and 1967 were the prequel to a period of dominance to follow for Bayern.

The first of those successes opened the door to a European adventure and a run in the Cup Winners’ Cup that ended with victory over Glasgow Rangers in extra-time. A maiden success in Europe wouldn’t be Maier’s last. A league and DFB-Pokal double was garnered in the 1968/69 season, followed by another cup success the following year. By now, the league was becoming Bayern’s competition of choice and three successive titles were secured from 1972, marking them out as one of the Bundesliga’s greats.

Not only did Bayern have the estimable Maier as their last line of defence, in front of him, Franz Beckenbauer was strutting his stuff in a libero position he would redefine, ably assisted by the robust Hans-Georg Schwarzenbeck and Paul Breitner. Further forward, Uli Hoeneß and Gerd Müller destroyed opposition defences. Despite the abundance of talent, Maier statistics for the period stand out.

In the first of the three successive title seasons, Bayern conceded just 38 goals across a 34 games. It was a total only bettered by runners-up Schalke’s tally of 35. It’s worth noting that the Bavarian club’s emphasis on going forward in that season also meant they topped Schalke’s goals scored by some 33%. The difference was emphasised by Bayern’s goal difference standing at 63, a full 23 better than their rivals

In the following season, the defence, with Maier in goal, would be even stingier. Opposition forwards were regularly shut out as Maier patrolled his box. In a season of 34 games, his defence was only breached 29 times. Considerably less than a goal per game, the team still registered 93 strikes at the other end. It was a mightily impressive performance and one that would be reprised the following term.

The dominant performances at home were echoed in Europe. Bayern’s first European Cup triumph with Maier in goal arrived in 1974. A shaky start in the first round, when only a penalty shoot-out brought victory over Swedish part-timers Åtvidaberg, preceded a 7-6 aggregate victory of East Germany’s Dynamo Dresden, before things got into gear against Bulgaria’s CSKA. In the semi-final, a 4-1 aggregate win over Újpesti Dózsa was secured thanks to Maier’s clean sheet in the home leg.

The final against Atlético Madrid was played at the Heysel Stadium in Brussels, with the first game ending in a 1-1 draw. Both goalkeepers had kept clean sheets into extra-time, but tired legs and brains were frayed around the edges as both conceded late. There were no penalty shootouts to decide the final in those days, and a replay was organised for two days later. Whilst Maier again prevented any goal being conceded, his opposite number at the other end failed to keep up the standard. Miguel Reina conceded four times across the 90 minutes as Bayern lifted the trophy.

As holders for the following year’s tournament, Bayern had a bye in the first round before facing East German opposition for the second time in two years in the shape of Magdeburg. This would be a different proposition from the games against Dynamo Dresden. Under the canny management of Heinz Krügel, Magdeburg had developed a young team driven on by a coach that, in more enlightened times, may well have made a fortune plying his trade at a top club in the west.

He had taken Magdeburg on an extraordinary run into Europe the previous season, and while Bayern were picking up European club football’s premier trophy, Krügel’s team had lifted the Cup Winners’ Cup, defeating holders AC Milan in the final. Bayern still managed to win both legs, though, to progress, underlining their mental strength as much as anything.

The semi-final tie against Ararat Yerevan of the Soviet Union would require a robust display by Maier in both legs. Playing in Munich first, entering the last dozen minutes, the game remained goalless. In such circumstances, concede at home and Bayern may well have had difficulties. Maier kept the visitors at bay, though, and two late strikes gave Die Roten something to defend when they travelled east.

Despite strong home pressure and the roar of 70,000 spectators in Yerevan’s Hrazdan Stadium, Maier and his defence kept the Armenian team to a single goal as Bayern squeezed into the last four and a semi-final against France’s Saint-Étienne.

This was a classic Les Verts vintage. Robert Herbin’s team was full of attacking potential who played with joie de vivre. They had secured the French league title by a clear eight points, winning 23 of their 38 games. In their attack they had the mercurial Dominique Rocheteau, an iconoclastic darling of the avant-garde left and the talismanic ‘Green Angel’ presence on the field who could intoxicate opposition defences in the same way as the spirit after which he was nicknamed.

The first leg was to be played in France and despite the pressing of the green shirts, Maier’s back line stood firm. Returning with a goalless draw was a highly credible result, but the job wasn’t yet done. Concede at home and Bayern would need to score twice to get into their second successive final. An early Beckenbauer goal eased the nerves of the home fans, but still a French strike would see them eliminated. Maier didn’t buckle, though, and when Bernd Dürnberger hit the second goal, with the home defence’s record still intact, the tie was done.

Going into the final, Maier and his defence had kept a clean sheet in five of the previous six European Cup games. Facing Leeds United in the final would be a challenge and a repeat of Maier’s achievements would come in very useful. Late goals from Franz Roth and Müller settled the game in Bayern’s favour as Maier ticked off another clean sheet. Bayern had retained the trophy in some style.

They went into the following year’s tournament having not secured domestic silverware for two seasons. Lose out in this competition and suddenly, the Bayern cupboard would begin to look a little bare. The club were also embroiled in the Intercontinental Cup. Pitched against Brazilian champions Cruzeiro, the first leg was played in Munich on 23 November. Yet another Maier clean sheet, coupled with late goals from Müller and Jupp Kappellmann, gave Bayern a two-goal lead to take to South America.

It would take a sound defensive performance in Brazil to keep the home team at bay. In front of 123,715 fans, the German nerve held and a goalless draw – and yet another clean sheet – made the journey worthwhile.

Borussia Mönchengladbach had won the Bundesliga and entered the European Cup as German champions, with Bayern’s place secured as holders. The Bavarians skipped through the first round, beating Luxembourg’s Jeunesse Esch 8-2 on aggregate before dispatching Malmö 2-1 to reach the last eight and a pairing with Benfica. A solid 0-0 draw in Lisbon and a crushing 5-1 home win meant another place in the last four. They would face the mighty Real Madrid.

Travelling to Spain in March, the Bavarians were in trouble early on when Roberto Martínez achieved the feat that had eluded so many other forwards, beating Maier to put the Spanish club ahead after a mere seven minutes. All of the German back line’s fortitude would now be required to stem the flow of attacks and keep the holders in the game.

In typical fashion, the task was achieved, and when Müller levelled the scores just ahead of the break, it brought the visitors a draw that was maintained until the end. Maier shut out the Spanish attack back in Bavaria and a brace from Der Bomber finished the job. Another European Cup final beckoned.

At Glasgow’s Hampden Park, Bayern met Les Verts again. It was hardly a classic. Bayern played solidly, comfortable in their defensive solidity, and struck at the opportune moment to win 1-0 and lift their third trophy. It had been an amazing run by the club and at the heart of it was their goalkeeper whose consistent, often breathtakingly brilliant, displays had played a fulsome part in delivering the triumph. Confidence in a secure back line had led to a pattern of play that was often more pragmatic than dynamic, but working to their strengths had brought the club ample rewards.

Maier would deliver similar assurance in the international arena. He would be selected for four consecutive World Cup squads, although his place in 1966 was merely as a back up to the established starter, Hans Tilkowski. By the time the next tournament rolled around, the position between the sticks was safely in the gloved hands of Maier. In the opinion of many pundits, the German squad that travelled to Mexico and eventually fell to Italy in what a plaque outside of the Azteca stadium describes as the Partido de Siglio (Game of the Century) was superior to the one that triumphed on home soil four years later.

In South America, there was a dynamic style to the German play that delivered copious amounts of goals, perhaps leaving too many gaps at the back. Five games brought no less than 16 goals, but at the back, 10 were conceded. While the Germans returned with honour and Müller collected the Golden Boot as the tournament’s top scorer, it was time for a rethink ahead of 1974.

Before that, there was a European Championship to complete. Played in Belgium, the competition at the time was very different to the jamboree experienced these days, with just four teams playing out semi-finals and a final to establish the winner. West Germany defeated the hosts 2-1 and then trounced an uninspiring Soviet Union side 3-0 in the final. Maier had his first international trophy.

Back on home soil, the German side that featured in the 1974 World Cup had a much more pragmatic style to it compared to the one that had plundered so many goals in Mexico four years earlier. Averaging more than three strikes a game in the previous tournament, this was shaved down to slightly under two in 1974, but the goals against column showed the benefit of a more balanced team. The two goals per game conceded in Mexico was reduced to less than one. It made all the difference.

In the first group fixtures, the only goal conceded was in the game against East Germany. It was an encounter that reached beyond mere playing ability for both fraternal and political reasons, and was therefore a far from normal encounter, with East Germany’s win a blip during a glorious summer.

The iconic defeat propelled West Germany into a more comfortable second group section and allowed them to progress fairly comfortably to the final, where they defeated Johan Cruyff and the Dutch Totaalvoetbal. Franz Beckenbauer lifted the trophy and Maier had a World Cup winners medal to add the European Championship one he had gained two years earlier.

The 1976 version of the European Championship took place in Yugoslavia and again comprised of just four teams. As in Belgium, the Germans defeated the hosts to move into their second successive final, where they would meet the tournament’s surprise side Czechoslovakia, who had defeated the Netherlands 3-1.

The Germans were twice behind in the game, before a goal by Bernd Hölzenbein squared things in the last couple of minutes. A penalty shootout would decide the event. It was here that the defining moment of the tournament occurred, when Antonín Panenka introduced his clipped penalty to the world. Whilst Maier gambled on a save, plunging to one side, a calm chip down the middle brought instant fame to the player and took the trophy to Prague. Maier had been the unwilling dupe in one of football’s famous images.

In 1978, West Germany crossed the Atlantic to Argentina as the World Cup’s defending champions. Still the automatic starting choice, Maier was now 34, and despite the longevity granted to goalkeepers over and above that afforded to outfield players, it was inevitable that his considerable powers would be on the wane. He was, however, still favoured above Hamburg’s Rudolf Kargus and Dieter Burdenski of Werder Bremen. It was a choice that few questioned.

Belying age and perceptions of an impending loss of ability, Maier played through the entire first group stage without conceding s goal. Things would change in the second stage. After another clean sheet in a goalless draw against Italy, the Germans faced their old foes, the Dutch, whose midfielder Arie Haan had been pressed into a defensive role in the 1970 tournament. He exposed the first chinks in Maier’s considerable armour.

Firing a long-range shot past the German goalkeeper to bring the scores level and put the first goal into the German net so far in the tournament, Maier suddenly seemed fallible. A second goal conceded would follow as the game ended in a draw. In the final match, Austria rode roughshod over their neighbours, defeating Germany 3-2 and ending the erstwhile champions’ interest in the tournament.

Perhaps the great man was on the slide, with calls from some quarters that a new goalkeeper should be tried. The debate was ended in the cruellest of ways. In 1979, a car crash delivered cruel injuries to Maier, forcing his retirement from playing. He had turned out in 536 league games, and just one short of 600 in all competitions, for Bayern Munich. He hadn’t missed a single league encounter for his club from the start of the 1966 season. He had featured 95 times for his country, was German Footballer of the Year three times (1975, 1977, 1978), was awarded the national service medal in 1978, and was recognised as Germany’s Goalkeeper of the Century.

Big gloves are somewhat akin to big shoes and although both Bayern and Germany have seen a succession of outstanding goalkeepers step up to try and fill them – Kahn, Lehmann and Manuel Neuer to name but a few – none have assumed the stature of Sepp Maier, and perhaps no-one ever will. He remains a legendary figure in German football and one of the greatest goalkeepers to ever play the game.

By Gary Thacker

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário